With a lengthy TBR, it’s sometimes difficult to finish reading a series: this year, with trilogies, I am exercising my completion muscles. Earlier this year, I went back and reread the initial volume of Margaret Drabble’s Thatcher trilogy and Judith Kerr’s Out of the Hitler Time trilogy, and then finished the other two volumes in each. Then I started and finished Stephen King’s Bill Hodges’ trilogy. So, it turns out that I can start and finish a trilogy in a reading year. Who knew?

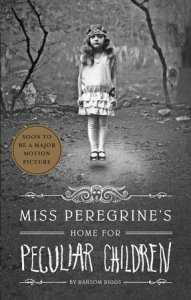

The Ransom Riggs’ volumes were all new to me, beginning with Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children (2011), along with Hollow City (2014) and Library of Souls (2015). When I found all three, in lovely new copies at the library, I knew the bookish universe was whispering that I should begin.

The Ransom Riggs’ volumes were all new to me, beginning with Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children (2011), along with Hollow City (2014) and Library of Souls (2015). When I found all three, in lovely new copies at the library, I knew the bookish universe was whispering that I should begin.

The series is plot-driven and features “Jacob Portman, boy nothing from Nowhere, Florida” in all three volumes (each of the first two volumes ends with a cliffhanger, so now you know that he survives each time, but I don’t think that’s much of a spoiler).

[Note: all quotes herein are from the first volume, largely in an effort to avoid spoilers, unless otherwise cited.]

But he is not actually a “sort-of-normal messed-up rich kid in the suburbs”: he’s peculiar. Without going into detail about how this is the case, or about the specific peculiarities of the other children he meets, here is a hint.

“’We peculiars are blessed with skills that common people lack, as infinite in combination and variety as others are in the pigmentation of their skin or the appearance of their facial features. That said, some skills are common, like reading thoughts, and others are rare, such as the way I can manipulate time.’

‘Time? I thought you turned into a bird.’

‘To be sure, and therein lies the key to my skill.’”

This is perhaps a little spoilery, but all of these ideas are included in even the most basic of the promotional materials for the series.

The hinge of trilogy turns upon this idea of transformation and, in particular, transforming time, which isn’t explained in detail in the novels either. In fact, it’s a common criticism of the series, that the mechanics of the time-travel or time-shifts are not consistent.

Perhaps this is true, but I am not the kind of reader who requires that kind of accuracy. To my mind, the series is much more about atmosphere and story-telling and the device upon which these turn isn’t the crux of the works.

Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children was actually inspired by a series of peculiar photographs, and the book grew up around them (the succeeding volumes, too). It’s easy to imagine that the author’s popularity grew faster than his world-building skills as an author.

Nonetheless, it’s clear that he had a lot of fun creating the stories of these characters’ lives. In the Q&A which follows the first volume he explains: “If I can’t know their real stories, I’ll make them up.” And as the series’ popularity grew, Ransom Rigg’s access to inspiration also grew: “The photographs came first, but I never stopped collecting. Even as I was writing the story I was finding more photographs to work in.”

Nonetheless, it’s clear that he had a lot of fun creating the stories of these characters’ lives. In the Q&A which follows the first volume he explains: “If I can’t know their real stories, I’ll make them up.” And as the series’ popularity grew, Ransom Rigg’s access to inspiration also grew: “The photographs came first, but I never stopped collecting. Even as I was writing the story I was finding more photographs to work in.”

He was not writing an instructive manual for time-slips, he was creating back-stories. Which occasionally surprised even him. One plot development so surprised him that he describes it as follows in the volume’s Q&A (I’m not saying which, so that you’re not looking for a big reveal in a particular volume): “When it occurred to me, I clapped my hands and cackled so loud it scared the cat out of the room.”

There are actually some fantastic creatures in the series, but it’s difficult to discuss them without spoilers. Here is a glimpse of the grimbears: “They are the preferred companion of ymbrynes in Russia and Finalnd, and grimbear-taming is an old and respected art among peculiars there. They’re strong enough to fight off a hollowgast yet gentle enough to care for a child, they’re warmer than electric blankets on winter nights, and they make fearsome protectors….”

But even though there are monsters in the book, it’s as likely to be a human being who behaves monstrously. And, in this case, it’s actually a building which is monstrous.

“What stood before me now was no refuge from monsters but a monster itself, staring down from its perch on the hill with vacant hunger. Trees burst forth from broken windows and skins of scabrous vine gnawed at the walls like antibodies attacking a virus – as if nature itself had waged war against it – but the house seemed unkillable, resolutely upright despite the wrongness of its angles and the jagged teeth of sky visible through sections of collapsed roof.”

As with Anne of Green Gables and many classic children’s quest tales, the idea of home – and a place to belong – is at the heart of the collection and this house straddles the desired and the feared. Some characters have a home, others do not and lament that if “…we were to take up arms against the corrupted and prevail, we’d be left with a shadow of what we once had; a shattered mess. You have a home – one that isn’t ruined – and parents who are alive, and who love you, in some measure.” (HC)

Often the ultimate threat is something more vague, amorphous: “The real danger then, wasn’t the figures on the platform, but the shadows that lay between and beyond them; the darkness at the margins. That’s where I focused my attention.”

Sometimes the threat is oblique, as in the descriptions of wartime life: “The kids applauded like onlookers at a fireworks display, violent slashes of color reflected in their masks. This nightly assault had become such a regular part of their lives that they’d ceased to think of it as something terrifying – in fact, the photograph I’d seen of it in Miss Peregrine’s album had been labeled Our beautiful display. And in its own morbid way, I suppose it was.”

Sometimes the threat is oblique, as in the descriptions of wartime life: “The kids applauded like onlookers at a fireworks display, violent slashes of color reflected in their masks. This nightly assault had become such a regular part of their lives that they’d ceased to think of it as something terrifying – in fact, the photograph I’d seen of it in Miss Peregrine’s album had been labeled Our beautiful display. And in its own morbid way, I suppose it was.”

But the novels offer an understanding of wartime from a peculiar perspective. And as Jacob ages, there is a slightly more reflective tone to the stories. “Despair was tangible here, weighting down everything, the very air.” Relationships grow more complex and there is more of a focus on internal action, an emphasis on mental states and emotional experiences. “Turbulent dreams, dreams in strange languages, dreams of home, of death. Odd bits of nonsense that spooled out in flickers of consciousness, swimmy and unreliable, inventions of my concussed brain.” (LoS)

The teenage perspective in the early volumes is less credible; sometimes Jacob’s thinking seems to suit a 30- or 40-something narrator instead. For instance, as a child of the digital age, I think he would be unlikely to use a metaphor like this one, even though it is quite striking: “Then, like a movie that burns in the projector while you’re watching it, a bloom of hot and perfect whiteness spread out before me and swallowed everything.”

But the emphasis is consistently on the story, and such details are likley less important to the target YA audience. “Just a story. It had become one of the defining truths of my life that, not matter how I tried to keep them flattened, two-dimensional, jailed in paper and ink, there woul always be stories that refused to stay bound inside books. It was never just a story. I would know: a story had swallowed my whole life.” (LoS)

These stories did not swallow my whole life: they read quickly and provided solid entertainment on some hot summer afternoons, and may provide an additional layer of enjoyment to the recent Tim Burton film.

As for other trilogies in the stacks, I’m still planning to finish reading Jane Smiley’s Last Hundred Years trilogy and Kelley Armstrong’s Nadia Stafford trilogy this year. But, then, good reading intentions abound.

Have you been reading books in a trilogy this year? Do you have a favourite trilogy? Or one that you might be tempted to read all-in-a-burst if the timing was right?

I have read and enjoyed the first two books in the series and hope to read Library of Souls eventually. The movie was fun, I thought! Even if it diverged wildly from the original story in the second half.

I wasn’t blown away by these books either. They were fun and light, but not nearly as impressive as other fantasy I’ve read.

Now that I know there will be a new trilogy that explores the world further, I am curious to see if the author will truly make his peculiar wold into something special and worth its hype.

I like Tim Burton’s stuff, so I’m interested in the movie, too. Did you feel like it diverged in an entertaining way that fit with the story but it just wasn’t the story? Or was it just plain entertaining? I’m not sure I’d mind either one, with Burton at the helm.

Maybe they weren’t actually intended to appeal to fantasy readers in the first place? Maybe that was a marketing gamble? After all, as disconcerting as some of the photographs are, I think most of them are of real subjects/situations, so if they were the initial inspiration, perhaps it’s more of a realism story that’s been bundled into another suit of clothes?

I love series books (mainly mysteries) but being that there are so many that I enjoy, I am rarely ever caught up on a series. This trilogy sounds so neat. I definitely would like to start this one.

I think you’d really appreciate the mood and atmosphere of these and, of course, the mystery which simmers beneath. There are some lovely fantastical creatures that one can’t really discuss without spoiles, but it’s fun to discover them (although the encounters are often the opposite of fun for the characters in the story)!

Im not great at finishing series either – I seem to want to spread them out over time and then forget to do so… The Miss Pegrine film is getting huge visibility – is it based on just the first book or the whole series?

I guess that’s been my issue as well, for I do intend to read on, just “not right now” but then “not right now” turns into “might as well be not ever”. Mind you, the fact that I keep having to reread early volumes, in order to move on, does seem to provide a kind of motivation at this point! (And it’s my understanding that the film is based on the first book only, but perhaps someone else here can comment if they’ve seen it.)

Are you still planning on starting the second book in November? I have it at the ready. I am hoping to finish my Laurie King mystery and pick up the next in line. Slow (very very slow) but steady there. I am not reading many mysteries at the moment, which is unusual for me….

Now it’s looking like later in November because I have a couple of really big reads ahead of me right now, including Steven Price’s By Gaslight. Is that one in your stack? I think you’d like it. It’s fun, but literary, but fun! How does “later November” sound to you for Smiley? Anyone else want to join in? You’d have plenty of time to finish the first volume before we start the second! 🙂

My daughter loves these books, but I can’t muster up the desire to read them. Although i did have a look through at the pictures, which turned me off even more. I also told her I wasn’t going to see the movie – she’s going to have to go with her friends! 🙂

I would love to read the Jane Smiley trilogy, though – that one’s more up my alley. And I’ve been tempted lately by the Annihilation trilogy. But our library only has the first book, which doesn’t make any sense. If I read them, I’d like to read them all at once, or I might never get past the first one.

It really seems to be a much more visual project overall to me. So if the photos don’t intrigue you, I’d say you’ve made the right call to choose another trilogy instead! I’ll be curious to hear what you think of Annihilation. I’m still afraid to read on. *chuckles*