So Iris‘ Dutch Lit month was in June, right? Many of you likely participated during June. Which, of course, was the point: a shared celebration of Dutch Lit.

I was planning to do that too. And I did have my copy of Hella S. Haasse’s The Tea Lords well ahead of time. (More about that novel another time.)

But it took me half the month to finally get to a particular library branch to gather the rest of my chosen reads, a series of books by Meindert DeJong, an author I adored as a young reader.

Then I needed to panic about the books that I’d borrowed two months previously, because their duedates were more pressing than those attached to the recent arrivals, which sat untouched until recently.

(Fellow library addicts will understand this, but I do maintain enough of a hold on reality to recognize that this is aberrant behaviour.)

In short, I dragged my reader’s tail, and I didn’t get to reading from this mini-collection of Dutch Lit until this past weekend.

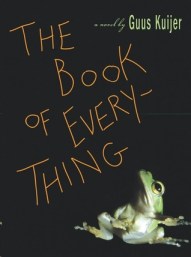

In the meantime, I also gathered a copy of Guus Kuijer’s The Book of Everything. Which, along with the copy of Haasse’s novel, and DeJong’s The Almost All-White Rabbity Cat and Shadrach comprised my weekend reading.

The up-side is that I do love reading in a burst. The down-side is that it was a solitary celebration (but the up-side of solitary celebrations is more cake for me).

What I loved about Meindert DeJong’s writing is still intact: his love of animals, the importance of relationships (familial and otherwise), and the sense of being in another world that was, nonetheless, enough like the world that I know to make experiences readily transferable.

(The Wheel on the School was one of my favourites; I re-read that one a few times from the library, and that’s the one book, in the stack pictured above, which is my own, collected years later, as an adult.)

Meindert DeJong’s The Almost All-White Rabbity Cat (1972)

Meindert DeJong’s The Almost All-White Rabbity Cat (1972)

Illustrated by H.B. Vestal

Barney is alone in a new apartment while his parents are at work, securing new jobs that will afford them opportunities that they didn’t have in the rural home they’ve left behind.

From the roof of the apartment building, which is seven stories high, Barney can see the river that reminds him of home. (There really isn’t much of a sense of this taking place in Holland: it could be any city, really.)

No, he’s not supposed to be on the roof. He’s not even supposed to open the door of the apartment. But an almost-all-white-rabbity cat invites itself into Barney’s space and then pulls him out of it.

Barney immediately feels a connection to the cat, who reminds him of the white rabbits he kept at home, in his grandfather’s barn, and he follows it through the building.

This not only reveals more interesting adventures behind closed doors, but leads Barney (and, eventually, his mother and father, too) through a series of events that lead them to reconsider what they miss from their home in the country and what true advantages the city has to offer.

The connections with the animals (not just Barney’s, but to say more would be spoilery) and the quirky behaviour of his mother and the secondary characters (there is an incident with a “hippie” which is funny to read now, as revealing as it is of the times in which the book was written) make this a satisfying re-read, though I might not have enjoyed it as much without that hearty dose of nostalgia.

Meindert DeJong’s Shadrach (1953)

Meindert DeJong’s Shadrach (1953)

Illustrated by Maurice Sendak

Davie’s grandfather has promised him a black rabbit, which will arrive on the following Saturday, on Maartens horse-drawn cart, when he makes his weekly rounds with the other goods that residents have requested.

It’s clear that not only does the story take place in another time, but it’s an overtly Dutch setting, evident from the caps in Sendak’s drawings, Davie’s wooden shoes, and the talk of canals and draught ditches.

What makes the story remarkable though, is the way the storyteller inhabits Davie’s experience, and that’s true regardless of the setting.

Davie is overwhelmingly excited at the prospect of having this rabbit, and because he knows a full week ahead, his excitement permeates every moment of his young existence.

This is true, too, for the reader, who has to wait half the book for the rabbit to arrive. The reader can taste the anticipation: it’s delicately but purposefully drawn.

The events of the novel are ordinary in the sense that Davie struggles to find the line between being a good son and grandson and pursuing the desires of his young boy’s heart.

The relationships, with his mother but especially with his grandparents are wholly credible, and the love for Shadrach, his rabbit (because, yes, eventually he does arrive) is palpable.

It’s a sweet tale which reminds me of the overall charm of Maria Gripe’s series about Josephine and Hugo.

Guus Kuijer’s The Book of Everything (2004)

Guus Kuijer’s The Book of Everything (2004)

Trans. John Nieuwenhuizen (2006)

Thomas’ story is framed as a story-within-a-story, with Kuijer having met with Thomas as an adult, an adult presenting Kuijer with The Book of Everything, which Thomas wrote as a boy.

(Perhaps I’ve missed something, but the only reason for the framework, that I can see, is to reassure readers that Thomas grows up to be happy, which is uncertain in the book he wrote as a boy as it chronicles a short period of time, shortly after World War II.)

The most striking element of the story is the question of resistance, as portrayed through Thomas’ experiences, in this own thoughts and actions, and in the events which unfold around him.

One layer of this transpires in a immediate sense, whether members of the family will resist the violence and control of Thomas’ father, who uses his Christian beliefs to justify striking his family.

Another layer exists more abstractly, referring to particular individuals in the community who resisted German control during the war.

Thomas is a sympathetic character, and there is a bookish aspect to the story that makes it particularly appealing, but the story will resonate most strongly with readers raised in or familiar with the Christian religion.

Favourite quote: “‘Heavens,’ Mrs. van Amersfoort exclaimed. ‘What are books about? They are about everything that exists.'”

It’s not likely as good as a Dutch Lit Month, but a Dutch Lit Weekend was pretty alright. Certainly better than No-Dutch-Lit-Ever.

Do you get behind like this too? Are you behind on something right now, reading this post when you should be reading some book or other instead? Off with you!

It’s nice to have company, being always behind!

DeJong’s books make for good comfort reading and I do appreciate that his adult characters take shape in a way which hints at more beneath the surface without stepping beyond the confines of creating believable children.

And, yes, Iris, now that you mention it, I think the book-within-a-book device does shield the author somewhat on the religious themes in the story; I did enjoy it, though perhaps not quite as much as you did. 🙂

I’m always behind on read alongs and other reading plans. And I never get to participate in all the events I really want to participate in.

I am very happy that you had your own Dutch Lit Weekend, that sounds like a fun few days. Do you know I have been racking my brain trying to think if I have ever read anything by Meindert de Jong, but I cannot really remember.. So I think I might not have. Perhaps I should give it a try sometime?

Like you, I felt the “book within a book” was done to let readers know that Thomas does grow up to be happy (though in a way the ending of the book gives you that hope as well). I wonder if it wasn’t a kind of safety net for the religious things as well?

Always behind. I have a copy of The Wheel on the School upstairs. It was one of the books my mother got for me one Christmas when I was a child. A great read.

Better late then never. Me, behind? Almost always! 🙂