Gallant, Gould, Jolley, Kenan, Proulx, and Walker

Short Stories in July, August, and September

Whether in a dedicated collection or a magazine, these stories capture a variety of reading moods.

This quarter, I returned to four favourite writers and also explored two new-to-me story writers.

The stories in John Gould’s The End of Me (2020) are short short stories, not postcard stories, but they average around four pages in length. There’s a journal prompt, an online book review, and a smell emanating throughout the basement suite of Mr. Dufort’s duplex.

A story might begin with the spark of inspiration that led a character to a career in marine biology but veer sharply into the events which led to his second career. There’s an obituary for a journalist who was fascinated by suicide, complete with a correction note at the end, stating that her dog had been incorrectly identified in the publication as ‘Rimbaud’ instead of ‘Baudelaire’.

Some days I would read three stories from the collection, one with each meal like a vitamin. On weekends I read longer stories (like Mavis Gallant’s or Annie Proulx’s–during this quarter I completed Paris Stories in my Gallant reading project).

I laughed at myself, my bookmark just past the halfway point in the collection, when I realized that the theme of the collection is perfectly encapsulated in the title: The End of Me. Isn’t that something, that a collection which revolves around death and dying would not be immediately and painfully recognized as such?

Sad but not morose, regret-filled but not melancholic: these stories are often entertaining (and always fleeting).

Often, too, they’re funny:

“What matters?” said the doctor. “What have you always meant to do? Swim with the dolphins? Lick Chateau d’Yquem from your secretary’s cleavage?”

Dan said, “I don’t have a secretary.”

“So, the dolphins.”

Sometimes they’re contemplative:

“I picture him, my grandfather, or I try to. Envision him. My grandfather, his father, his father’s father, and so on. I turn around and go the other way, forward in time but by a different route – I picture me if my settler forebears hadn’t fled their own lives, if they’d never overrun this land and leached into my bloodstream. I picture me at home here. I picture me at home anywhere, a stranger to nothing.”

Sometimes, they offer the unexpected: “By the time you read this, I’ll still be alive.”

In the same story, you might find both The Tibetan Book of the Dead and a Woody Allen movie (Sleeper, if you want to know). There are references to Born Free and Star Wars, Gogol and Tolkien, to Kierkegaard and Liszt and Van Gogh. There are gardenias for prom night and there’s half a joint in a tampon box. There’s a wife with “a laugh like a cat after a bird it can’t quite reach” and a mother who loved reading hardboiled American mysteries but looked “more than part of an Agatha Christie character”.

There’s a character who is “all limb, his torso a knot at the hub of his pipe cleaner physique”, like “pulled taffy”. And a student writing to his music teacher: “It would be an exaggeration to say that I think of you whenever I breathe, but you did change my attitude to the air that moves in and out of me, and I suspect there’s nothing more fundamental.”

Maybe you think that a mugful of stories about death and dying could use a dash of sugar, but there’s a hint of Simon Rich and a pinch of Etgar Keret, and at least there’s no arsenic.

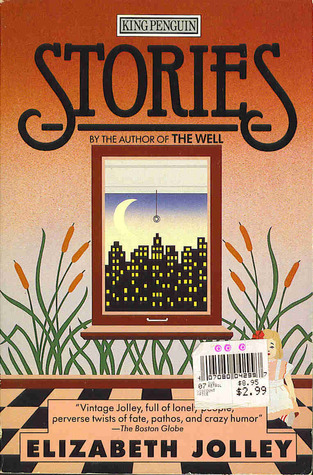

In Elizabeth Jolley’s Stories (1984), the first six stories are drawn from The Discarders, which the author describes as presenting “the human being overcoming the perplexities and difficulties of living”. Whether it’s a crazy world or it’s our world: Jolley isn’t sure. There, they have “too much shy hope and tenderness and expectation” and they discard each other rather than the “values of our society and education and the repeats on television”.

Even though this family is hardly welcoming (not even to its own members), this set of stories remains the highlight of this collection for me. However, a few stories later, “A Hedge of Rosemary” appears, which Jolley explains is the first story written in Western Australia, around 1960.

That’s remarkable in and of itself, but the author’s ruminations on its contents intrigues me too: “I suppose it contains things I had left behind, like the old man who carefully studied the soles of his boots whenever he took them off, and things which were new to me but known already by people who had always lived here”. But it’s also, she says, “a re-enactment of the reality of transplantation and chosen exile” as experienced, vicariously, by a child.

I wrote about Randall Kenan’s new short story collection for The Chicago Review of Books in August; news of the author’s death, a few days after my piece was finalized, hit me hard. Over the summer, I’d spent a lot of time on the page with him. Not only this new collection, but his earlier fiction and non-fiction. (Any fan of James Baldwin will want to seek out Kenan’s writing on Baldwin in particular; his passion for the writer and his work is remarkable.) Getting acquainted with his backlist over several weeks felt like getting acquainted with him. Rereading his short stories felt like returning to a pet topic in an ongoing conversation. Albeit a one-sided conversation. One of the facets of Kenan’s work which suits me perfectly is his gradual and determined reconstruction of the community of Tims Creek: his novel, A Visitation of Spirits (1989), and his earlier collection of stories, Let the Dead Bury the Dead (1993), are all set there. While I was reading, I imagined all sorts of future Tims Creek stories. But for those who thought there would be only two books, at least this third will offer some comfort.

The eleven stories in Annie Proulx’s Close Range: Wyoming Stories (1999) vary substantially in length, from a few pages to forty pages. Throughout, her prose is direct and gives the impression it was edited repeatedly for concision. Which isn’t to say that the sentences are always short, the grammar technically correct. Take the beginning of “A Lonely Coast”: “You ever see a house burning up in the night, way to hell and gone out there on the plains?” She plots the shortest path, but if it’s the shortest path to developing characterization or creating atmosphere, that might take more telling. One of the shortest stories, “Job History” encapsulates years of a man’s life. In “The Mud Below”, one of the longest, the scenic detail creates a series of vivid and densely constructed scenes. If your only experience of Proulx is her sprawling epic, Barkskins, the length of these works will surprise you, but thematically her work is all-of-a-piece.

Alice Walker’s In Love & Trouble (1973) is an early but representative collection in her oeuvre. The subtitle ‘Stories of Black Women’ serves as a herald of the collection’s contents, but also as a reminder, that society and the publishing industry have made efforts towards representation and amplification of voices in the past. Many of these stories address issues which have recently resurfaced in the media as though freshly unearthed—the prevalence of domestic violence, the exploitation of young women by abusive opportunists—as well as the pain that arises from fractures in bonds of friendship and kinship.

Two of my favourites here are “Really, Doesn’t Crime Pay?” and “We Drink the Wine in France”, both of which feature smart, bookish women. In the former, Mordecai encourages the narrator to allow him to read her stories: “I will see if something can’t be done with them. You could be another Zora Hurston—“he smiled—“another Simone de Beauvoir.” And in the latter, Harriet “will read every one of the thick books in her arms, and they are not books she is required to read. She is trying to feel the substance of what other people have learned. To digest it until it becomes like bread and sustains her. She is the hungriest girl in the school.”

The Alice Walker collection sounds so interesting! I have such a hard time with short story collections. I feel like I can be too picky with them, but maybe I’m not reading the right ones. What short story collection would you recommend to try? I’ve been trying to find some ones with lighter content, or with a shorter page length.

Some of Walker’s stories are really short, so you might enjoy them, but they are often serious and sometimes heavy. I also recommend this collection, because the stories fit well with a cup of coffee (only a couple are longer than that) and I think the only complaint you might have is that the characters feel so real that you want to “see” more of some of them. For lighter fare though, B.J. Novak’s One More Thing might suit you; they’re very entertaining and smart, and the only risk is that you might want to gulp them, but reading too many of them at once would be like eating too much candy.

I have previously read Alice Walker and Annie Proulx (didn’t particularly gel with her though) but not their short stories though. I like the sound of the Elizabeth Jolley collection though. I’ve not read any short stories for a while, I must get back to them.

The Color Purple is one of my favourites, and I’m glad she’s written so many stories, but I love Alice Walker’s essays and poems (which is not the usual way of things, with me). I know what you mean, some habits just slip away, while we’re trying to juggle under these strange new circumstances we inhabit now. I’ve made a little list of them (the ones I’ve noticed) and am gradually trying to get them worked back in the mix; it’s fun with book-related habits, maybe not-so-much fun with some other kinds of (er, cleaning-related?!) habits!

I’m just about to start reading the Gould. I thought about waiting until after I’ve read it to read your thoughts, but I couldn’t wait. (I also know that you don’t give things away.) So, now I am looking forward to them even more.

Other short stories? The three from the Giller longlist, as well as People Like Frank by Jenn Ashton and Nothing Without Us. That’s quite a few at once for me!

I like the subtitle of Ashton’s collecton “…and other stories from the edge of normal”. I’m still waiting for my copy of Dominoes from the library, but I know you loved it so much, that I’m thinking about “borrowing” from the grocery budget to buy a copy instead. I have the idea that it’s a little like The Party Wall, in terms of the ways the stories intersect: am I off-base?

No, that’s right. I mean, it’s very different from The Party Wall, but it’s true there are overlapping characters and settings in the stories. Like an egg hunt! You’ll probably end up flipping back and forth and marking lots of spots.

Sounds like a keeper. I see Kellough’s backlisted books at the library are now also in demand. Nice to see a small-press writer finding fresh readers with a prizelisting.

Love it!

Your first three authors are unfamiliar to me, but I like the sound of Gould’s themes. I’ve read a novel, nonfiction and poetry by Walker (one volume each, I think), but no short stories, and I own two Proulx novels but have somehow never gotten around to her.

I think you might enjoy Randall Kenan for the linked Tims Creek stories and the role that the church plays in many families’ lives. I was hoping that this new collection would bring fresh attention to his craft but, with his death, readers must now be contented with what’s been published.

I have a review copy of The World Doesn’t Require You by Rion Amilcar Scott — I wonder if Kenan may have been one of his inspirations?

Ohhh, thank you so much for mentioning this. It sounds terrific and I can see that I added it to my TBR in 2019 but I’d forgotten about it. (I just read this conversation, with Danielle Evans, at LitHub.) At first glance, I’d guess Edward P. Jones might have been more influential given that Kenan’s stories don’t reach very far into the past (and there’s a Washington D.C. connection because Scott and Jones) but who knows what/who inspires writers. LOL I’ve only read one of Jones’ collections and the occasional story besides, but I want to read everything he’s written (he should be on my MRE list)!

I requested the Scott mostly for the Maryland connection. I tried the first story earlier this year and didn’t get anywhere, so it’s gone back on the shelf to await the right time. I enjoyed Jones’s short stories — that’s another good comp. There’s a touch of magic realism to the Scott, though.

GTK, thank you, now I’m even more curious! My card is labouring under a couple of heavy reading assignments right now, and stressed by various prizelist reading (which you know all about, having inspired a few of the Women’s Fiction Prize winners on there), but hopefully by the end of the year I can request a few of these newish books, recently added to my TBR.

Over the past couple of years, I’ve been reading – and enjoying – short stories more and more. I’m on my ninth book of them this year. They’ve included Willa Cather, Alice Munro, W.O. Mitchell and others. I think my favourite was Natasha by David Bezmozgis although I thought The End of Me was brilliant and was very interested in your feelings about it.

Natasha is one of my favourite collections too. His newer collection is just as good. With The End of Me, did YOU know, going into it, that ALL of the stories would revolved around this theme?! Once I realized it, I couldn’t believe I’d overlooked the title’s significance, but the stories felt so alive and engaging.

Does the Annie Proulx collection include Brokeback Mountain? It’s the only story of hers that I’ve read (in a mini ‘single’ booklet), but I’ve often thought about trying others…

Yes, it does, it’s the final story. I read it independently too, at some point, with a movie-tie-in cover: maybe that’s the edition you read as well. I loved The Shipping News.