Seth launched his own comic book, Palookaville, in 1991. That’s where readers first met the Matchcard brothers.

The 2019 Drawn & Quarterly volume includes these earlier stories (distinguishable by stylistic variations) and substantially expands this family’s story.

The brothers’ relationship is defined by their respective relationships with the family business, selling electric fans: Abe and Simon, one more involved, one less involved. The story opens in 1997, with an older Abe, musing how he’d often thought he “was a man in step with [his] time” but hadn’t realized he was “looking backward”.

Abe ruminates on all conversations he had with other salesmen over the years: “Stories filled with perseverance, quick thinking, and just plain hard work.” When he contemplates his legacy, he recalls all the “fragile pieces of paper scattered all over the province”.

These yellow papers with his signature prove his existence. (That, and this nearly-five-hundred-page-long comic.)

It’s ironic, he thinks, that he considers himself to have lived in the “real world”, in contrast to his brother, Simon, who remained at a distance, increasingly preoccupied by caring for their mother.

As though Clyde Fans was somehow apart from the “real world” in Abe’s view. But now he thinks differently about what’s real and what’s not, what matters and what falls away. (There’s a curious and strangely poignant subplot about novelty postcards that echoes this theme.)

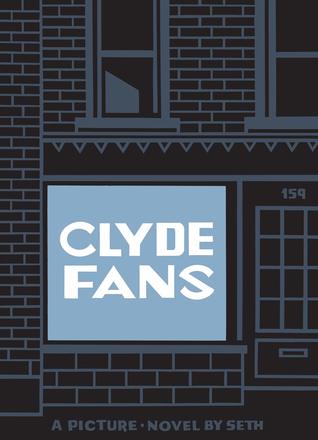

The author’s note for this volume explains that the idea for the comic came from peering into a window downtown Toronto, the scene just like it’s drawn in the comic, complete with the two portraits on the wall.

This is a quintessential Canadian story, with frequent mention of small towns (like Sarnia, Thunder Bay, and Arkona, Ontario) and frequent and open references to Canadian experience. (“I doubt I’d be any more isolated in snow-bound cabin in the Yukon,” for instance.)

The time moves from 1997 back to 1957, 1966 and 1975. The radio news in 1997 warns of snow and discusses both a curling championship and Eaton’s Department Store’s attempts to evade bankruptcy.

The mention of changing business practices via Eaton’s (the movement away from catalogue order and department stores to in-person shopping and boutique retail models) is relevant because business at Clyde Fans began to deteriorate with the greater availability of air-conditioning technology.

But the theme of decay also plays out on the personal level, in Abe’s inability to establish relationships outside of the family and in the boys’ mother’s cognitive decline, into dementia.

One pivotal scene in 1957 presents Simon in the Bluebird, a diner in Dominion where he orders grilled cheese with potato salad and a coffee for dinner. There, he overhears two older women, talking about the weather, until one of them reminisces about her husband, Freddy, stopping to change a flat tire and leaving the woman and her friend, Esther, to wander off into the bush where they stumbled on the most enchanted place.

“I doubt I’d be able to find it again even if I tried,” she laments. (Her “clearing in the bush” description could be a subtle reference to the classic Susanna Moodie volume, for another jolt of Canadiana.)

The waitress is watching the clock, Simon is chewing his sandwich, and the other woman at the table shares a similar story. OOH, this is simply another instance of how we recognize the extraordinary in the ordinary; OTOH, this scene replays later in the volumes and has a peculiar importance all its own.

The panels are contained and exact (increasingly so in the comics of recent years) and the palette is consistent throughout, only occasionally a full-page image for scene-setting (interiors, cityscapes, landscapes) or emphasis (often black with a single phrase or face).

The style is reminiscent of The New Yorker’s cover art in the 1930s and 1940s (the artist’s work has graced three issues of The New Yorker) and the hardcover compilation is complete with a window cut into the cover on the front and, in the back, a photograph of the author pictured in front of the real Clyde Fans storefront.

But none of that looks as real as this story feels.

This book is a nominee for the 2020 Giller Prize. This post follows a format I first used in 2012. Prizelists invite readers to peer more closely at current publications; they can spark conversation, draw attention to hard-working writers, and encourage readers to look beyond these lists to the many, many other works of quality that are not included on longlists. Reading the longlisted books represents less than 5% of my year’s reading. Read widely and share your favourites!

Giller-bility

This is the first year graphic narratives have been included in the Giller longlist. Recognition for a work like this, underway for well over two decades wouldn’t be misplaced. But it’s been years since the small-town experience was prioritized (say, in Alice Munro’s Runaway, the 2004 winner and Richard Wright’s Clara Callen, the 2001 winner).

Inner workings

On the surface, this volume appears to be all about what’s on the page. And there are so many pages. So many panels. Some pages look like advent calendars, each page with so many square windows on it, each filled with an image. (The entire catalogue of fans, for instance, and so many close-ups of lonely and sad and anxious faces.) But story-wise, the most significant pages depart from these patterns, focusing on emptiness and space.

Language

Language

It appears as though there’s as much text in the first 100 pages as in all the rest of the pages. As the artist’s style evolves, he depends more heavily on the image to transmit the emotions which, in the earlier comics, reside in the narrative (like the passages quoted above). Certain words recur, like echoes through memory, but mostly the language is functional, plain-speech.

Locale

Locale

Dominion is familiar territory for Seth. The model of this fictional town he’s built has been shown in art galleries and is also featured in this NFB documentary. But Dominion could be Anytown. Fans of Chris Ware’s comics will find themselves at home in this territory: ordinary people living their lives in ordinary spaces.

Engagement

Engagement

The bulk of the action in Clyde Fans is inaction: reflection and contemplation. If this story doesn’t appeal thematically, it’s unlikely to hook readers. There are panels blackened so only the character’s thoughts show, and the entire first part revolves around Abe’s self-directed monologue of memory: “Simon and I, our lives didn’t seem to have much of a plot. Perhaps all lives are like that—just a series of events with little meaning.”

Readers Wanted

Readers Wanted

Maybe you don’t ask for much, but you dream a lot.

Once, along a roadside, you found an enchanted place.

You prefer the cool breeze of a desk-fan to the chilling roar of an A/C unit.

One pleasure of walking at night is the ability to peer, unobserved, into other people’s windows.

I’ve been looking at Clyde Fans by googling Images. There seems to be lots of going to the bathroom. I think that you’d really have to be in to it to understand the layers of what’s going on, that it wouldn’t reward casual reading. But I hope it does well in the Giller (apparently it hasn’t), I’m happy to accept that graphic novels can be literary.

Hah! Now I want to see your Google search results! LOL I think you’re right, that it’s the kind of story meant for the long-haulers (trucking pun intended! :)), and there is an abundance of ordinary detail. One part that I really enjoyed is the struggle of an introverted person to perform in sales. I’ve experienced that kind of intense fish-out-of-water feeling in the workplace at times and I could relate to the strain (not being able to walk away from the job, in the brothers’ case, it’s their family legacy, in mine it was about paying the rent).

The search results gave me lots of full pages I could expand and read through, and with your commentary I could sort of guess what was going on. I worked as a salesman off and on for years, with indifferent results. I am ok at selling stuff I am making myself (transport solutions mostly) but terrible at selling anything else. And constantly putting yourself forward to strangers .. ugh!

Ooohhh, I see what you mean now. You can get a good sense of the style and tone that way. I was a little surprised by just how much is available, but perhaps by virtue of it having been a work-in-progress over such a long period of time. You raise a good point, selling one’s own goods or services is a different thing. Yes, it’s the cold-calling thing that has always been a problem for me: ugh, indeed. And, yet, I enjoy stories set around the conceit of a travelling salesman, I mean a contented travelling salesman, a character that offers glimpses into a variety of spaces otherwise unseen.

I see this morning that it sadly didn’t make the shortlist. A graphic work is probably still much of a stretch for the jury, although I do give them full marks for including a short story collection (LOL)

Will you give them double-full marks then, for having included two? 😀 Even though I know I should pay more attention to the shortlist, I am ultimately so long-list focussed that I actually forgot that yesterday was the SL announcement. I’ve read all five of the SLed books, but I think I’ll read on with the longlisted books I have now anyway.

I can check off everything under the Readers Wanted category.

Despite my struggles with reading graphic novels, I’m very curious about this one!

LOL Well, then you’re in a shoo-in to fill the position: I’m sure the book will hire you in a flash!

This might be the graphic novel to change your mind: lots of familiar CanLit themes, and an abundance of text in 1997 volume, by which time you’ll probably be invested in the family’s story.