The call for witnesses in The Stone Diaries resonates throughout Shields’ work:

“Life is an endless recruiting of witnesses. It seems we need to be observed in our postures of extravagance or shame, we need attention paid to us. Our own memory is altogether too cherishing, which is the kindest thing I can say for it.”

The solution? “Other accounts are required, other perspectives, but even so our most important ceremonies – birth, love, and death—are secured by whomever and whatever is available. What chance, what caprice!”

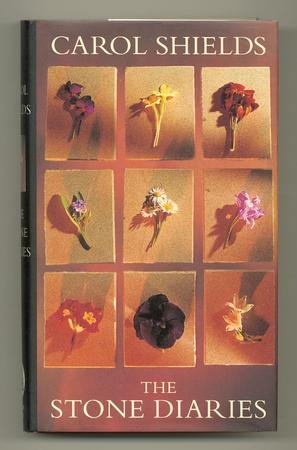

Rereading The Stone Diaries, I was surprised to find that the photographs, the element that most tickled my fancy on my first reading of the novel some years ago, do not play a particular role in the novel.

They are simply another set of witnesses, recruited. Another way of engaging us, as readers, cast in the role of witnessing, further.

This time, I enjoyed the language, with Mercy “a woman whose desires stand at the bottom of a cracked pitcher, waiting” and sorrow that “sings along the seams of other hurts, especially the old unmediated terror of abandonment”.

And I admired the callback to the growth of The Box Garden, with this:

“She may yearn to know the true state of the garden, but she wants even more to be part of its mysteries. She understands, perhaps, a quarter of its green secrets, no more. In turn it perceives nothing of her, not her history, her name, her longings, nothing—which is why she is able to love it as purely as she does, why she has opened her arms to it, taking it as it comes, every leaf, every stem, every root and sign.”

Which also led back to half of Happenstance, wherein Brenda observes Barry’s “remarkable hair”: “Coarse as grass, with its own energy.

Originally published in two separate volumes—1980’s Happenstance with Jack Bowman’s story and 1982’s A Fairly Conventional Woman with Brenda Bowman’s—the two books were republished as a flipbook with each character’s perspective designated to each of the book’s halves. “What chance, what caprice!” Indeed.

One passage that I noted in my initial reading of Happenstance that still made me laugh this time was Jack’s desperation to avoid working on his book: “There was nothing he could do to contravene the certainty that awaited him: a whole solid clock-ticking afternoon buried alive in the dark, lonely den with that goddamned book.”

In contrast, Brenda is naturally compelled to work on her quilting, an activity she undertook by accident (like Larry discovered his love of mazes). Her work makes her feel alive, whereas Jack feels buried alive by his.

But what I truly delighted in, rereading this pair of novels about marriage, were the descriptions of snow. Even in Happenstance, viewed through Jack’s controlled and measured response, he perceives the wonder in the snowfall:

“Franklin Boulevard was buried. This was real snow; he hadn’t seen snow like this for years. Well over a foot it looked like, and the drifted peaks around the sides of the houses and trees had the Dream Whip perfection of snow that he remembered, probably falsely, from childhood. Forts, tunnels, towers, miracles of possibility.”

Admittedly, I like this passage for the simple snow-ness of it. I recognize that “Dream Whip” perfection. I’ve built those forts (their rooves mostly caved in, long before any chance of melting).

But I also admire the subtle nod that Shields’ crafting offers attentive readers. Because in the Brenda half of the book (and in the recent editions, readers can choose to begin with either spouse’s version, whereas on first publication Jack’s story was first), readers learn that Jack often mentions that Brenda is more likely to fall on the side of realism.

“In their early married days, when her husband Jack made these claims for her sense of reality, he was, she suspected, stating something else as well: that he was not a realist, That his vision of things was romantic, withheld, speculative. Thee was such a thing as allegory, there was such a thing as metaphor, there were the rewarding riches of symbol and myth. There were layers and layers—infinite layers—of meaning.”

But, that’s actually not the case, as readers learn. In fact, when readers have an opportunity to compare Jack’s view of the snowfall with Brenda’s, it’s clear that hers is the more romantic view.

“She pulled the curtains, and there it was, everywhere. It was still falling; the sky was filled with heavy wet flakes. They drifted slowly past the window, reminding Brenda of bars of music, densely harmonic. Long rectangles of snow clung even to the blank glass office-building across the street (who would have thought there were places on that smooth face that could catch and hold these slim shapes). The smaller brick building next to it (a bank?) as softened by its white covering, the flat roof transformed to an untouched field, rural-looking, a farmer’s pasture. The sky was surprisingly radiant, a sheet of photographic film, whitish-gray with a backing of silver, and far below Brenda could see the narrow street choked with drifts.”

In this strange year, when we have all been forced to slow and reflect on our immediate surroundings in a way which stands in contrast to previous years, this idea of witnessing holds a peculiar meaning.

Shields’ writing reminds me of the importance of our own private, small ceremonies, of the urgent need to tend our box gardens, of the strange wonder of happenstance, the importance of partnerships, the miracle of entering and emerging from the maze, and the quiet moments of astonishment that cannot be captured in stone.

That was one of the things that gave me the most to think about after reading Happenstance… The order of the two stories. How would I have experienced the book differently if I had read Jack’s perspective before Brenda’s? I love how you picked out the passages about snow!

You know I love snow! And, side-note, how is it that your comments on my most recent post and this month-old post, have both come through on the same day?! Were you saving it or something? LOL

I got behind on your posts over the holidays, so I’ve been reading one of your older ones along with your newer ones until I meet in the middle! Almost there! 🙂

That’s a good way of doing it; when I fall behind, I tend to start with the “oldest” and than it takes me forever to feel like I’m part of the conversation again.

I’m sure I’ve commented on this before, but I’ve never read any Carol Shields. I know! It’s a tragedy that I really feel, especially when you post such beautiful reviews and passages from her books. I love stories told from two different perspectives, this sounds fantastic!

You’d’ve seen this one reviewed on Naomi’s blog at some point too; I think she and Literary Wives discussed it, maybe even some time last year.

Yes, sounds familiar. And I’m sure I made the same “I’ve never read her sucks to be me” comment LOL

A lovely post about two of Shields novels. I have only read one Shields novel before, Unless, ages ago, so can’t remember much about it. I must try her again one day.

When you do get to her again, you will wonder why you waited. But you have been reading a lot of good books and writers in the meantime too!

What a great post on Carol Shields. I’ve read a couple of her books and have a few others on my shelf just waiting. Maybe I’ll get to them this year!

Maybe you will: those mysteries are awfully seductive though. Like chocolates: one always tastes like one more.

You are making me want to reread Shields! It’s been a while, long enough. The question is, which one to begin with?

Just leaf through and let your intuition guide you; it was the opening lines of one of her early novels that convinced me to start rereading them. And if you don’t allow yourself to take time for rereading, it won’t just happen. 🙂

Again, a lovely post, that impressed me with your memory – I’ve read The stone diaries and The box garden but not way would I, if I reread The stone diaries now, remember any link to The box garden though I did enjoy that book when I read it. She was a lovely writer. Sad that she’s gone.

It helped that I had my notes from some of my first readings of her novels. I probably wouldn’t have drawn out The Box Garden connection either, had I not reread it for #1977Club and then again earlier this year, after Small Ceremonies.

I love your final paragraph and how you’ve been able to apply her work to life now (and through the years). It’s been a pleasure reading and rereading Shields with you this year!

It was so lovely to have company with (most of) my rereading: thank you for joining in with the fun. And it was so reassuring to see how little each of us remembered (and what strange details/aspects) from earlier readings, just impressions mostly.

“In this strange year, when we have all been forced to slow and reflect on our immediate surroundings in a way which stands in contrast to previous years, this idea of witnessing holds a peculiar meaning.” I in fact sped up, to fill the endless tedium of isolation, of repeated isolations from April onwards. And with mostly just audibooks from previous years and decades to keep me company I found myself detached, not from political life, which I follow omnivorously on Australian and US websites, but from family life and cultural life, to the extent that I have no idea what writers have been doing in 2020.

I am glad that has not been your experience. You did a wonderful job reflecting on your re-reading of Cat’s Eye. I had to have recourse to Wiki to see who Carol Shields was. i love the idea of the husband and wife story being published back to back. SF used to be published that way sometimes but not with related stories

[Edited to add Link to Wikipedia]

It feels to me as though we were all forced to slow down with the lockdowns, whether we elected to slow or not. But you raise a good point that, in response to the shut-down, reflecting on the new and uncomfortable reality did send many into various dizzying directions and I know you’re not alone in having responded with a flurry of unexpected activity (where others were playing with sourdough starter, you were listening to audiobooks on 1.75 speed LOL).

Myself, I didn’t “enjoy” the slowing that a lot of people seemed to (binge-watching on streaming services, long walks, and staring contests). That actually sounded like a “nice problem to have”, to me. Nothing really changed in the day-to-day of our household, except that everybody knew that we didn’t have to commute so we should be able to work more/harder each day (and, not complaining, because we were lucky to have work, even if it hasn’t paid what it “should”). At least you can now enjoy the fruits of those efforts; your governing officials curtailed the spread in a way that our regional leaders did not (a mini-Drump rules this province).

I’d love to do a mini-project on flipbooks! I know I’ve read a couple but can’t think of their titles just now. Shields is a writer I think you’d really enjoy. She’s all about relationships (usually marriages) and isn’t all that far from the Sally Rooney of her day (now, I’ll wait for someone, maybe Rebecca or Susan, to say nooooooo, to that).

Nice review. I can’t say it is reading I would normally be interested in — focused more on the connectedness of all life — but your references to style and wordsmithing arouse my curiosity. There is always more to learn 😉

Regarding your insight about the witnesses aspect of our human bubble, what came to mind is the ancient ones’ hand prints and stencils 😉

It’s easy to take the women writers of Margaret Atwood’s generation for granted, but if she had not persisted it would be much harder for women writers to get works of literary fiction published and recognized. And that’s doubly true for Canadian women writers; her generation (including Michael Ondaatje, Brian Moore, Matt Cohen, Mordecai Richler etc.) put Canada’s literary scene on the map.

If she had not had a childhood filled with bugs and trees, lakes and tents, she probably wouldn’t have grown up to write the tremendous eco-fiction she’s penned more recently. (The Maddaddam books, yes, but also the shorter works, fiction and poetry, that are showing up in so many places, designed to motivate and inspire other humans to take responsibility for making changes that count.)

Your comment about the petroglyphs reminded me of Leanne Betasamosake Simpson’s latest book, Noopiming: The Cure for White Ladies. It’s a hybrid form, but these markings play an integral role in the “story”.

I have yet to read Carol Shields – no idea why I haven’t yet – but the quotes above are excellent.

Of the two, I think you’d enjoy The Stone Diaries more. The way she assembles a life is less straightforward. But I think you might enjoy Swann more, in the end, because it does include a bit of poetry and the process of assembling a life is even more of a puzzle.